Indigenous History on Babson Meadows in Riverdale

By Mary Ellen Lepionka, 2022

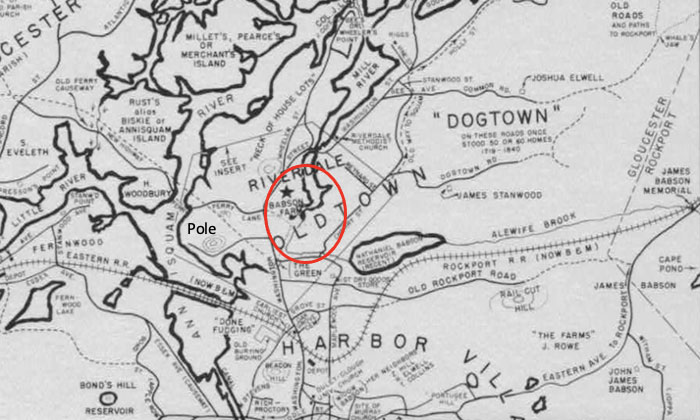

The Babson Meadows were along Poplar Street facing Mill Pond, Mill River, and the Babson Farm. Mill River begins as Alewife Brook, originally known as Wine Brook for the color of its water, reddened by the bog iron in the soil at its source in Dogtown’s Briar Swamp. Mill River joins the Annisquam River beyond Wheeler’s Point to meet the sea. Gloucester’s first mill was built at Beaver Dam on Alewife Brook in 1642, followed by a sawmill in 1652 on Mill River and a corn mill in 1677. The Meadows included land that became the southern end of Cherry Street, part of Washington Street, and a portion of the original “Gloster Plantation”, today the site of the White-Ellery and Babson-Alling houses, Cape Ann Museum Green, and Grant Circle. The Babson Farm, formerly the Pearce Farm, was on the other side of Mill River just to the west.

Map with circle around area of Riverdale.

The Babson Meadows, Fitz Henry Lane, 1863

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester MA

The Babson and Ellery Houses, Fitz Henry Lane, 1863

Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester MA

John Low Babson (1812-1898), a grocer in Riverdale, bought the Colonel William Pearce farm at auction in 1881. John was the son of the Gloucester sea captain Nathaniel Babson (1784-1836). John’s son, Osman Babson (1842-1908), with his wife and sons, succeeded him at Babson Farm. In turn, their son, Elmer Warren Babson (1874-1944) became a veterinarian and established an animal hospital on Babson Farm land, and his son Osman (1908-1973), named after his grandfather, followed in his father’s footsteps. The Dr. Osman Babson Road from Washington St. past the O’Maley Innovation Middle School to Cherry Street is named in his honor.

Pearce Farm in 1869, E. G. Rollins photo, Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester

The land that became Babson Meadows and Babson Farm had been used by Indigenous people for generations before European contact. The Pawtucket had settlements all around Cape Ann, with a main village that the colonists called Wonasquam in Riverview between the Annisquam River and Mill River. Wheeler’s Point was an Indigenous shell heap, an accumulation of meals from thousands of years of occupation. Pole Hill just to the west of the Babson Meadows was a ceremonial gathering place and sky observatory for people living in Riverview as early as 3,500 years ago. By around a thousand ago, Riverdale was planting ground for Algonquians growing maize, or “Indian corn”.

In 1638 John Endicott bought the Riverdale land that became Babson Meadows and Babson Farm from the Pawtucket, the Algonquian people who were living there at the time. Endicott wrote to John Winthrop, governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, that he had “bought” “the hoed ground” in what would become Riverdale from the “Indians” for a plantation, in exchange for bushel baskets of the corn the Pawtucket would have grown on it. The Indigenous people, however, understood that transaction differently from the Europeans who purchased their land. They did not believe that the natural environment was a commodity that could be bought or sold; they thought they were granting permission to use the land for a period of time. As a consequence, the people at first did not realize that deed signing would lead to permanent dispossession of their homeland.

By purchasing “the hoed ground.”, Endicott acquired land that the Pawtucket had already cleared of trees through slash and burn, mixed the potash from the burned wood into the soil, and removed roots and stones. Algonquian farmers in southern New England cleared much more land than they put into production in any one year, for the purpose of developing the soil before planting in it. Without other fertilizer or irrigation, to have some assurance of future harvests, they needed to build up soil depth in mounds to retain moisture over time. They prepared extra land also because corn is a heavy nitrogen feeder and needs new soil to grow in every two or three years. Not understanding the native economy, the colonists regarded unplanted fields already prepared for cultivation as wasteful and the land as unneeded surplus. Other English plantations in Massachusetts, such as Ipswich and Newbury, also were established on “the hoed ground” of the Indigenous people.

Pawtucket cornfields also lie under the Gloucester Public Works Department, Veteran’s Way, and the O’Maley Innovation Middle School parking lots. In the late 1930s, an avocational archaeologist, N. Carleton Philips, conducted excavations of Indian sites in Gloucester. He never published his work but in 1940 reported his findings to the Gloucester Rotary Club. In his surviving notes for this talk, he describes the village in Riverview and a site in Riverdale in the “old Babson pasture east of Riverview.” In the “old Babson pasture” he found eight wigwam floors, “discernable to this day,” with utilized stone and fire pits containing burned wood, acorns, clams, and 23 potsherds. These house floors are not discernable today, but in 1938 Philips saw the patterns of discoloration of the soil that to archaeologists indicate the presence of postholes and hearths.

The wigwams in the Babson Meadows would have housed eight extended families, between 30 and 50 people in all. For most of the year the women and young children would have been chiefly occupied with tending cornfields; keeping kitchen gardens, in which they grew native squashes, pumpkins, melons, beans, tobacco, and sunflowers; and gathering wild food plants, herbs, and shellfish. The men and boys would have been hunting in Dogtown, which was forested with old growth trees at the time; fishing; tending trap lines; quarrying stone; conducting trading (or raiding) expeditions; and clearing land.

The Pawtucket used fire both to clear land for cornfields and to manage forests. They conducted controlled burns of forest undergrowth in the late fall in conjunction with an annual communal game drive. The practice also promoted the growth of fire-resistant trees and trees with edible nuts, such as white oak, hickories, chestnut, beech, and white pine; as well as forbs with heat-enabled germination, such as blueberries, huckleberries, and cherry trees.

The Indigenous people of Cape Ann traditionally were seasonal migrants, but by around 1400 they had established year-round villages on the coast. The populations of the villages would rise and fall dramatically with the seasons as other subsistence and cultural resources became available. The Pawtucket never relied on sedentary agriculture alone but maintained a mixed economy in this region with its abundance of rich and diverse natural resources. Nevertheless, as they gave, leased, sold, or lost their land to English colonists, Indigenous people also lost their autonomous means of subsistence. The lack of any reference to them in Gloucester’s official historical records, as well as in John J. Babson’s history of Cape Ann, suggests that their dependence on the colonial economy and government was ultimately at their peril.

John J. Babson’s history, p. 45:

[W]e should allude to the absence of all evidence that Cape Ann was ever the seat of any Indian settlement. Its Indian name was Wingaersheek. Skeletons of the aborigines have been found; the Indian tools, and collections of clam-shells, discovered many years ago around one spot in Squam, indicate the presence of Native people at some time in considerable numbers: but whether their visits were frequent or rare, and whether the early settlers were welcomed to a friendly wigwam or alarmed by the menacing gesture and suspicious carriage of the red man, no record or tradition is left to tell.

Alas, the historian did not have access to other documentary and archaeological evidence of Indigenous presence on Cape Ann, and did not know that “Wingaersheek” is not an Algonquian name for Cape Ann but the (misheard) name of the beach the family lived on whom John Endicott’s surveyors had interviewed. The Pawtucket of Cape Ann and elsewhere in southern Essex County were on good terms with the colonists and remained neutral in conflicts. They became victims of extreme prejudice against Indians, however, following King Philip’s War of 1675-1676. Wonasquam Village was finally abandoned in 1686. Memory of the Indians was subsequently erased from records and from the land, but descendants of Indigenous people who had assimilated still live here. Acknowledging today that Babson Farm and the Babson Meadows were Pawtucket homelands represents a measure of social justice.

The sources for this article are:

Alling, Robert Babson

1959 (1930) Robert Babson Alling Ancestors, Descendants, and Close Relations, Chicago: https://archive.org/stream/robertbabsonalli00alli/robertbabsonalli00alli_djvu.txt.

Babson, John J.

1860 History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Ann: Including the Town of Rockport, Samuel Chandler, Procter Brothers, Gloucester MA.

Babson, Katherine L.

2019 Babsons and Universalism, Babson Historical Association: https://babsonassoc.org/babsons-and-universalism/.

Babson, Thomas E.

1950 Riverdale Story: A Family Scrap-book of the forebears and descendants of Osman and Marcia Babson, Gloucester MA.

Cutter, William R.

1908 Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of Boston and Eastern Massachusetts, Volume 2, Lewis Historical Publishing Company, New York.

Felt, Joseph B.

1862 Indian Inhabitants of Agawam: Read at a Meeting of the Essex Institute, held at Hamilton, August 21, 1862. Essex Institute Historical Collections 4: 225-228; Biographical sketch of John Endicott; Opinions on Winthrop and Endicott and who was the first governor of Massachusetts. Essex Institute Historical Collections 5:73, 8: 96, and 15: 298.

Gloucester Daily Times

1940 Cape Ann Rich in Indian Relics Rotarians Told N. Carleton Phillips, 23 samples of pottery from Riverview, November 13, 1940.

Kimmerer, Robin W. and F. K. Lake

2001 Maintaining the Mosaic: The Role of Indigenous Burning in Land Management, Journal of Forestry 99: 36-41.

Leavenworth, Peter S.

1999 “The Best Title That Indians Can Claime”: National Agency and Consent in the Transferal of Penacook-Pawtucket Land in the 17th Century, New England Quarterly 72 (2): 275-300.

Lepionka, Mary Ellen

2013 Unpublished papers on Cape Ann Prehistory, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 74 (2): 45-92.

2017 Algonquian Shellfish Industries on Cape Ann, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 78 (1): 28-40.

2020 Native Agricultural Villages in Essex County: Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Evidence, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 81 (1-2): 65-90.

Lepionka, Mary Ellen and Mark Carlotto

2015 Evidence of a Native American Solar Observatory on Sunset Hill in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 76 (1): 27-42.

Stewart-Smith, David

1994 The Pennacook Lands and Relations: An Ethnography, The New Hampshire Archaeologist 33/34.

Massachusetts Archives

Volume 113, Towns: 1693-1729 (incl. Gloucester Records 1642-1874), Massachusetts Archive Collection Microfilm A 632, Massachusetts Archives, 220 Morrissey Blvd., Boston.

William, Salem

1905 Some account of the Agawam Tribe, in George Francis Dow, ed., Essex Institute Historical Collections 4: 225; 6: 208.

Winthrop, John

1790 Journal of the transactions and occurrences in the settlement of Massachusetts and the other New-England colonies, from the year 1630 to 1644, written by John Winthrop … and now first published from a correct copy of the original manuscript, Elisha Babcock, Hartford CT.