Indigenous Presence in Dogtown

By Mary Ellen Lepionka

The Babson family handed down and bought land in the southern section of the Cape Ann heartland known as Dogtown, encompassing parts of both Gloucester and Rockport. Property acquired in 1927 by the economist Roger Babson (1875-1967) and his cousin Gustavus Babson (1882-1941) included sites rich with the history of a now-vanished colonial settler community – but also rich with prior Indigenous history.

The pre-Contact and colonial era presence of Indigenous people in Dogtown has long been denied for presumed lack of archaeological evidence. In a 1984 report of the Massachusetts Historical Commission, for example, the authors dismiss the very idea of it:

There have been a number of attempts to ascribe an American Indian presence or habitation to Dogtown prior to Anglo-Saxon settlement, but there exists no archaeological evidence to this effect. Wabanaki, Penobscot and other Maine and Massachusetts groups of Algonkian stock came only seasonally to Cape Ann and they preferred to camp in sheltered places in Annisquam, Bay View and West Gloucester just above the shoreline where they fished or dug for clams or mussels and where ample evidence of this inhabitation has been and continues to be uncovered. Romantic fantasists who see in Dogtown’s boulders a counterpart to Stonehenge and other Druidic ritual sites have wished also to locate primitive rites and practices here among the barren spaces between Dogtown’s dolmen. Such practices exist, however, only in the imagination of those who are drawn to the peculiar quality of Dogtown’s light, the underbrush that clings to its gravelly soil and to the seemingly ageless geologic formations….

Since that time, archaeological discoveries and the modern reinterpretation of the Indigenous history of Essex County have made it clear that Cape Ann was fully occupied by Indigenous peoples beginning as early as PaleoIndian times more than 12,000 years ago. An important PaleoIndian site recorded in Dogtown is Site 19-ES-64 near Alewife Brook on a terrace below Railcut Hill in Gloucester. This is inside the western boundary of Dogtown on land that became part of the Blackburn Industrial Park.

Artifacts and ceremonial stone landscapes of Middle and Late Archaic Period people (10,000 to 3,500 years ago) have also been discovered in the watershed area spanning the northern part of Dogtown from Annisquam Heights and the Goose Cove Reservoir watershed to Pool Hill and the Pool Hill Forest in Rockport. Later Woodland people–the Algonquians, most recently the Pennacook-Pawtucket–lived on Cape Ann year-round prior to the Contact Period. They had agricultural settlements, with a main village in Riverview, and their sites contain broken ceramic vessels and horticultural tools. They grew Indian corn, squash, beans, sunflowers, and tobacco.

The Algonquians would have used Dogtown as a hunting ground for white-tailed deer, muskrat and beaver, fox and fisher, weasel and ermine, squirrel and cottontail, and other creatures. Dogtown’s turtles, snakes, frogs, hawks, kestrels, and waterfowl would have been important in cultural expression as well as for food. Dogtown was a source of other important cultural and subsistence resources as well. The people would have gathered the cranberries, blueberries, grapes, mushrooms, cucumbers, acorns of the white oak and other nuts, arrowhead and waterlily and wood lily bulbs to roast like potatoes, and all-purpose plants for both food and fibers, such as staghorn sumac and cattail. They would have gathered and rolled the mast from dogbane, milkweed, and thistle stalks for their cordage and weavings, and collected sacred plants, such as cedar and sweetgrass, for the spiritual protection of their wigwams.

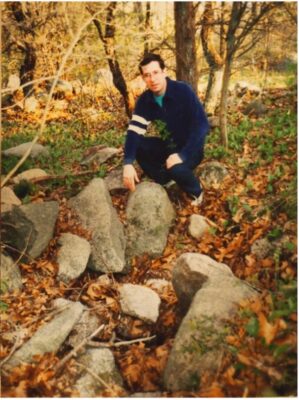

Their shamans and healers would have looked for medicinal plants in Dogtown, such as sassafras, purslane, pipsissewa, mullein, jewelweed, cinquefoil, nightshade, and many others. And the giant boulders in Dogtown, such as Peter’s Pulpit and Whale’s Jaw, would indeed have had spiritual significance to them. In their animism-based belief system, such stones contained spiritual power and were sentient. Other boulders and bedrock crevices were the homes of spirits. The people constructed ceremonial gathering places and astronomical observatories with groupings of stones and used stones to mark the locations of springs and drainages and groundwater flows. In 1991 the archaeologist Irving Sucholeiki identified this stone grouping at a spring in Dogtown as Indigenous in origin.

Their shamans and healers would have looked for medicinal plants in Dogtown, such as sassafras, purslane, pipsissewa, mullein, jewelweed, cinquefoil, nightshade, and many others. And the giant boulders in Dogtown, such as Peter’s Pulpit and Whale’s Jaw, would indeed have had spiritual significance to them. In their animism-based belief system, such stones contained spiritual power and were sentient. Other boulders and bedrock crevices were the homes of spirits. The people constructed ceremonial gathering places and astronomical observatories with groupings of stones and used stones to mark the locations of springs and drainages and groundwater flows. In 1991 the archaeologist Irving Sucholeiki identified this stone grouping at a spring in Dogtown as Indigenous in origin.

There is other artifactual evidence as well, although most finds ended up private collections. In the 1930s Foster Saville explored Dogtown on horseback collecting Indian artifacts. Later, N. Carleton Philips, Frederick Norton, and others also reported finding stone artifacts in Dogtown. Archaeological surveys from 1918 (Frank Speck and Frederick Johnson) to 2019 (Public Archaeology Laboratory) confirm pre-Contact Indigenous presence in Dogtown. Roger Babson may not have known about this when he was making his extraordinary contributions to the well-being of the people of Cape Ann.

In 1606 Samuel de Champlain sketched this woman pounding corn in a log mortar. He notes in his diary that he saw her on Cap des Isles, the Cape of Islands, the name he gave to Cape Ann. Indigenous people were still here when the English settled 20 years later. An old street name for the end of Dennison Street in Gloucester, where it winds into Dogtown, was Samp Porridge Road. The name refers to an Indigenous corn mill operation on Samp Porridge Hill during early colonial times. The Pawtucket were making a cereal from corn meal there, called nausamp.

In 1606 Samuel de Champlain sketched this woman pounding corn in a log mortar. He notes in his diary that he saw her on Cap des Isles, the Cape of Islands, the name he gave to Cape Ann. Indigenous people were still here when the English settled 20 years later. An old street name for the end of Dennison Street in Gloucester, where it winds into Dogtown, was Samp Porridge Road. The name refers to an Indigenous corn mill operation on Samp Porridge Hill during early colonial times. The Pawtucket were making a cereal from corn meal there, called nausamp.

English settlers were early drawn to the resources of what would become Dogtown Common.

The historian John Babson (1809-1886) proposed that settlers were initially attracted to the interior of the Cape for its proximity to the first mill, built at the second of two falls on Cape Pond Brook, later operated by William Ellery. Dogtown Common with the numerous cellar holes of colonists who had created a community there in the 1650s.

Remnants of the dam, the cellar of the miller’s house, and the foundation of the original wooden canal could still be seen in the 1980s, along with vestiges of the fall, built near the corner of Poplar and Cherry streets in Gloucester on land that was once part of Babson Meadows. “Thus these two small falls on Cape Pond Brook which still runs through these pastures,” Babson concludes, “were an important factor in locating this original settlement….”

1642 mill dam and mill race in Dogtown, Massachusetts Historical Commission

The Dogtown settlement was at its peak in the 1750s with 80 or so comparatively affluent families but was gradually abandoned after the Revolutionary War. With a decline in population and prosperity, and relocation to the coast, the houses in Dogtown Common came to be occupied by war widows, rented to minorities and people of lesser means, or left vacant to squatters. The last house was torn down in 1845 and the last resident taken to the poorhouse. Roger Babson wrote about the settlers, made a map of their cellar holes, and was among the many collectors who for generations made a hobby of digging in the cellar holes for colonial artifacts.

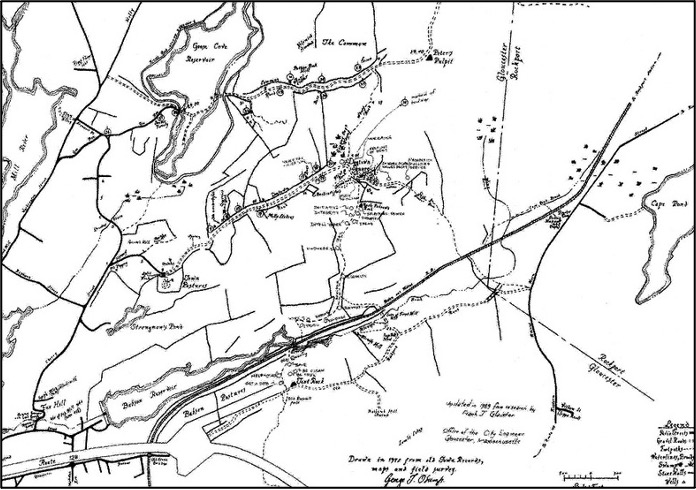

Babson land and the Dogtown settlement, detail from George Odum’s map, 1817, City of Gloucester Archives

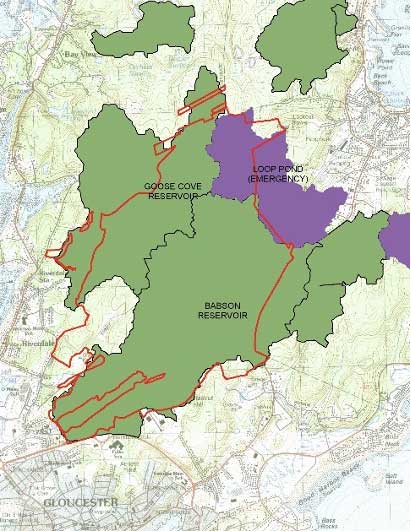

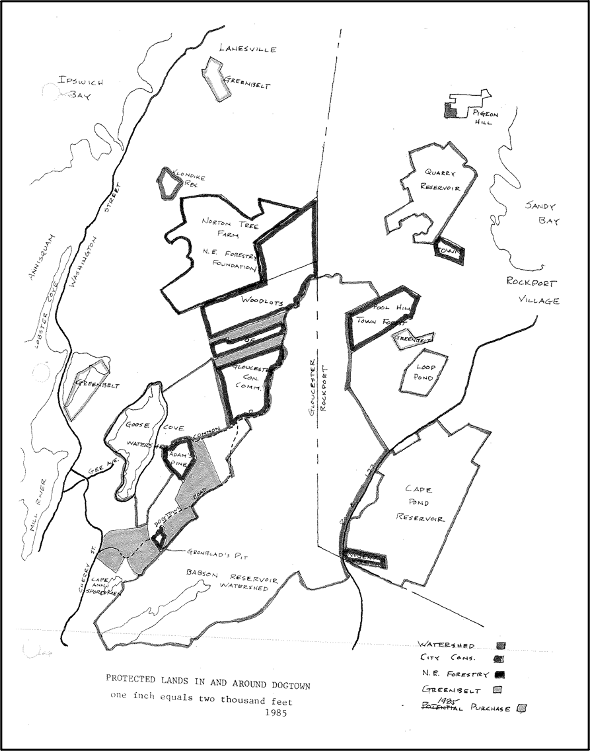

Cape Pond Brook and Alewife Brook flowed through Babson land in Dogtown, which also contains Briar Swamp, Granny Day’s Swamp, and other wetlands that are the source of Cape Ann’s water supply. In 1930 in response to a water shortage, Roger and his cousin gave about 1,000 acres of this watershed to the City of Gloucester for the construction and maintenance of a reservoir, on the stipulation that the area would forever be kept as a public park, protected from development. The Babson Reservoir Dam was built that year.

Dogtown Watersheds, Courtesy Cape Ann Trail Stewards

Hand drawn map showing properties around Dogtown.

Building of Babson Reservoir 1930

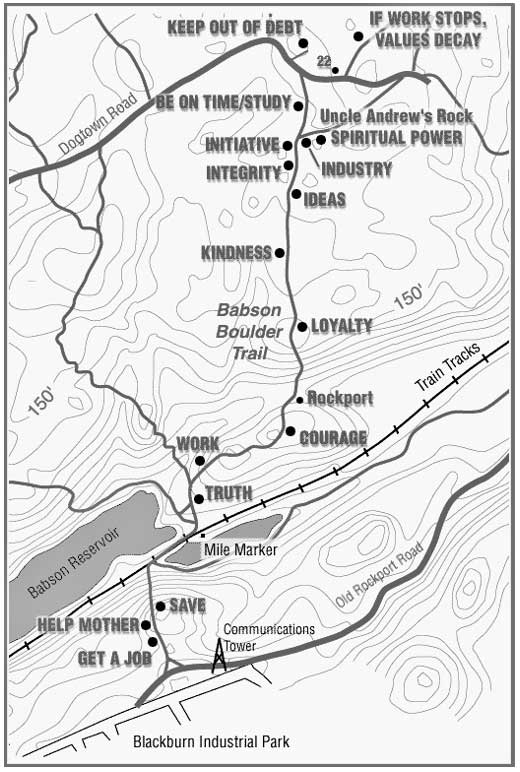

The Babson Reservoir and the Commons cellar holes remain destinations for hikers on Dogtown’s network of trails, including the popular Babson Boulder Trail. During the Great Depression, in another act of charity and against his family’s wishes, Roger Babson employed 35 out-of-work Finnish stonecutters to carve words, numbers, and phrases into granite boulders, glacial erratics dotting a trail. The 6.5-mile trail with 23 carved boulders runs north-south between Old Rockport Road and Dogtown Road.

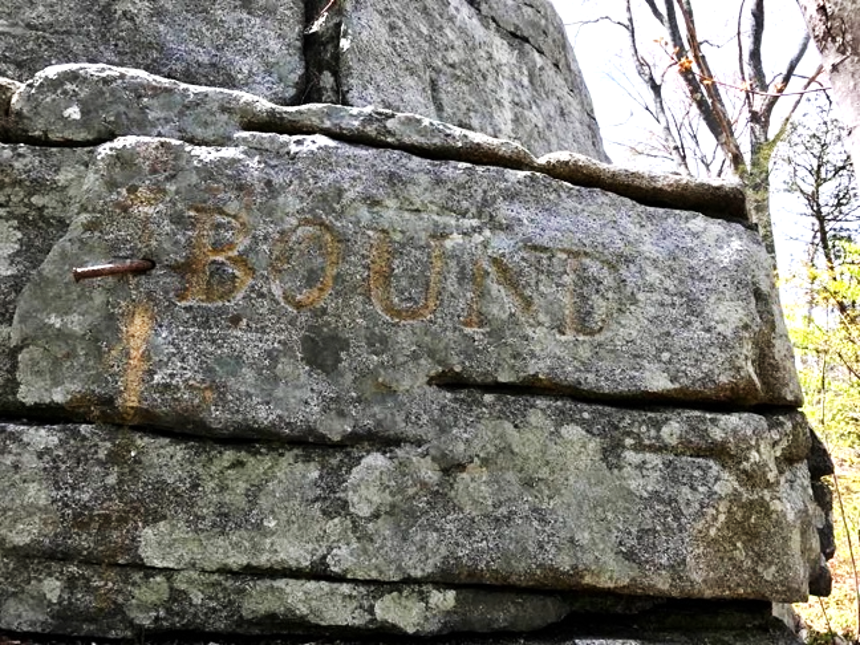

Babson Boulder Trail and Boundary Marker

Babson Boulder with BOUND inscribed.

The sources for this article are:

Antiques and Auction News

2019 The Career, Research and Collection of Frederick H. Norton, Antiques and Auction News, e-Edition, August 9, 2019.

Babson, John J.

1860 History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Ann: Including the Town of Rockport, Samuel Chandler, Procter Brothers, Gloucester MA.

Babson, Roger W.

1927 Dogtown: Gloucester’s Deserted Village. Leo A. Chisholm, Gloucester, MA.

1949 Actions and Reactions: an Autobiography of Roger W. Babson (Rev. ed.), Harper and Brothers Publishers, NY.

Babson, Roger and Foster Saville

1936 Cape Ann, A Tourist Guide. Cape Ann Bookshop, Gloucester, MA.