Indigenous History on the Babson Cooperage Site

By Mary Ellen Lepionka

In his 1860 history of Gloucester, John Babson wrote: “…[W]e should allude to the absence of all evidence that Cape Ann was ever the seat of any Indian settlement.” That judgement has been passed down unquestioned from generation to generation to the present day. He was mistaken. But evidence of Indigenous settlement on Cape Ann had to wait until the development of modern archaeology after the Civil War and the field of Cultural Resource Management in the 20th century.

Babson also wrote: …”[N]o record or tradition is left to tell.” In this he was partially correct. Information about the Indigenous people of Cape Ann is absent from town records, erased or expunged from the archives by the time Babson was writing. Brief notes in Selectmen’s minutes from 1682 and 1684 refer to “the Indians who live among us.” Otherwise, other than archaeological evidence, we have only a few informal accounts and anecdotes in the letters and memoirs of later residents (such as Ebenezer Pool’s papers, John Dunton’s letters, and Charlotte Lane’s memoirs). “Erasure” of Indigenous life here has occurred in many other coastal New England towns as well.

Yet Native people had been an enduring presence on Cape Ann for thousands of years. If John Babson had been privy to the knowledge we have today, he would have understood that thousands of years ago, when Sandy Bay and Stellwagen Bank were dry land, Indigenous people were here to hunt mastodons and caribou. Later, as river mouths and forests were drowning in sea level rise, creating estuaries, Native people came to gather shellfish and to hunt for fur seals and walrus. When early European colonists dug cellar holes in Annisquam, they disturbed Indigenous burial grounds and unearthed the skeletons, stone tools, and shell heaps that were evidence of Indigenous settlement.

The unearthed remains were those of Algonquians known as the Pawtucket, or Agawam Indians. These people had lived in wigwams along Alewife Brook, which runs through Dogtown from the Cape Pond wetlands to Mill River – on what would later become Babson lands. Unbeknownst to John Babson, the history of his Cape Ann ancestors was intertwined with the hidden history of Cape Ann’s Indigenous peoples.

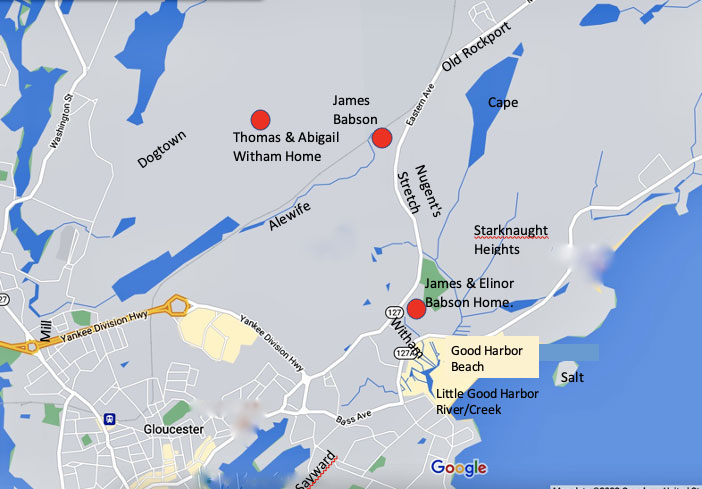

In 1658 James Babson, son of Cape Ann Babson matriarch Isabel, was granted a 12-acre beaver meadow and 20 adjacent acres of woodland that are part of Dogtown today. James built a cooperage or barrel-making shop there on Alewife Brook, about a mile above Beaver Dam and Cape Ann’s first mill, a sawmill erected in 1642. James and his wife, Elinor Hill Babson, and their ten children lived nearby in a house near the intersection of today’s Eastern Avenue and Witham Street on a parcel that is now Calvary Cemetery.

Today the James Babson Museum commemorates the site of that seventeenth-century cooperage. The Museum fronts Eastern Avenue (Rte. 127), also known as Nugent’s Stretch after one of the farm families that owned the area. The forerunner to the present road was a foot path leading to Sandy Bay–Old Rockport Road–and cartways to Good Harbor Beach and Gloucester Harbor. An Indigenous family lived on the cartway that became Witham Street, the route for transporting cooperage barrels to boats waiting on Good Harbor Beach, called Starknaught Beach at the time.

Other Pawtucket lived on the saltmarsh along Sayward Street above Little Good Harbor Creek and on the freshwater swamp at Starknaught heights. There is no trace of them in these places, but according to the society pages in local newspapers, their descendants made pilgrimages to these and other ancestral sites on Cape Ann during the 19th century. They camped on Sayward Street, Phillips Avenue in Pigeon Cove, Lighthouse Beach in Annisquam, and Rust Island.

When James Babson built his cooperage in the mid 1650s, he was likely familiar with his Pawtucket neighbors. Babson was a miller and cooper. He made barrel staves and built barrels in his shop to supply the growing fishing industry. Staves typically were cut from oak and shaped and secured with hoops of different diameters made from hickory or chestnut saplings. An ox-cart would haul the finished barrels to the beach to be ferried to Salt Island to be filled with salt, or to Cape Ann’s fisheries to be packed with salt cod, or to mills to be filled with barley flour for export to the Caribbean, where barrels were needed for the products of slave plantations. In 1665 the salt-works on the small island just off Good Harbor Beach was still in operation.

The Indigenous family on Witham Street may have been employed to help load and unload the barrels at the shore. At other times, they would have fished there, setting weighted surf nets in the channel for mackerel and bass and tide nets in Little Good Harbor Creek for herring and smelt. They would have dug quahogs on the beach, gathered lobsters and crabs, and canoed out to Thacher’s Island to raid the rookeries there.

James’ and Elinor’s daughter Abigail married Thomas Witham of Gloucester, and after James’ death in 1683 Elinor gave the Babson Farm at Little Good Harbor to the couple. This perhaps is when the ox-cart path from the cooperage to the beach became Witham St. The Indigenous family that had been living there may have left in 1686 with the other Pawtucket when the village of Wonasquam in Riverview was abandoned. King Philip’s War–Plymouth Colony’s war against the Wampanoag had ended just ten years before, and it had become impossible for Indigenous people to live openly or freely in Massachusetts.

In 1688 Cape Ann colonists who were veterans of King Philip’s War were granted 6-acre lots on Sandy Bay and in West Gloucester, Magnolia, and parts of Dogtown. That same year Massachusetts issued its first bounties on Indian scalps. James’ and Elinor’s son, Thomas Babson, fought in King Philip’s War in Capt. William Turner’s Company in campaigns in Hadley Massachusetts and the defense of Hatfield. His brother John received Thomas’s land grant in Kettle , awarded in honor of Thomas’s service, for he did not live to enjoy it. Thomas Babson was lost at sea in 1679 at the age of 21.

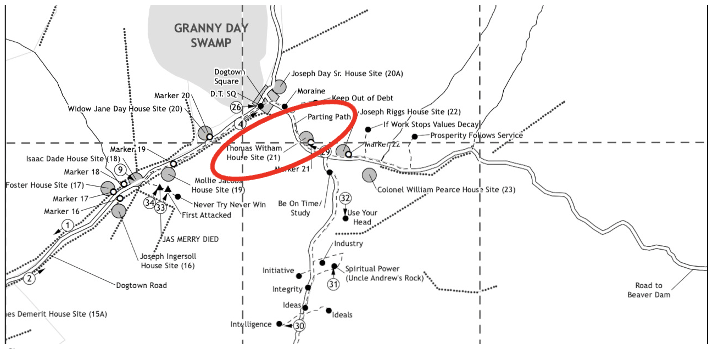

The 1688 disbursement of 6-acre land grants was extended to all white men of legal age living in Gloucester at the time. The 82 house lots laid out were assigned by lottery, but it was perhaps no coincidence that Thomas Witham’s lot was at a site linking Dogtown’s roads to the Babson Cooperage. The Thomas Witham House Site, built circa 1693, is north of Dogtown Road, south of its intersection with Dogtown Square along the Parting Path. He and Abigail lived there, today a cellar hole marked by a Babson Marker Stone.

In 1697 Thomas Witham sold his farm at Good Harbor to John Ring. A succession of new owners followed, outlined in detail on the web site of the James Babson Museum. The stone structure at the site of the cooperage today, made of locally quarried granite and recycled wooden beams, was built in the 1830s by Dr. John Manning as a barn. Its Babson history resumed in 1928 when Roger Babson and his cousin, Gustavus, purchased the property, rebuilt the barn, gave the land to the City of Gloucester, and opened the James Babson Museum in 1931.

John Babson may have been unaware, with the evidence available in his time, but Cape Ann was indeed a “seat of Indian Settlement.” His own ancestors in Gloucester and Rockport had lived on land inhabited and shaped by generations of Algonquian Indians. What John Babson did not know we can now acknowledge.

Map showing red dots at Thomas & Abigail Witham Home, James Babson Cooperage and James & Elinor Babson Home.

Map drawing with red circle around Thomas Witham House Site.

The sources for this article are:

Abbott, K. M.

1904 Old Paths and Legends, Gloucester 1639-1873: 175-185, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

Andrews, J. Clinton

1986 Indian fish and fishing off coastal Massachusetts. Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 47 (2), 42-46.

Babson, John J.

1860 History of the Town of Gloucester, Cape Anne, including the Town of Rockport: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=ORhFAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.

Babson, Roger and Foster Saville

1936 Cape Ann Tourist Guide. Cape Ann Bookshop, Gloucester , MA.

Babson, Thomas E.

1855 Evolution of Cape Ann Roads and Transportation, 1623-1955. Essex Institute Historical Collections: XCI-1955, pp. 302-328.

Bentley, William. Joseph G. Waters, Marguerite Dalrymple, and Alice G. Waters, eds.

1914 The Diary of William Bentley: Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts, The Essex Institute, Salem MA.

Bragdon, Kathleen

1996 Native People of Southern New England, 1500-1650, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman OK.

Cape Ann Scientific and Literary Association

1923 Along the Old roads of Cape Ann. F. S. and A. H. McKenzie, Gloucester, MA.

Cutter, William Richard

1915 New England families, genealogical and memorial, The original lists of persons of quality; emigrants; religious exiles; political rebels; serving men sold for a term of years; apprentices; children stolen; maidens pressed; and others who went from Great Britain to the American Plantations, 1600-1700 with their ages and the names of the ships in which they embarked, and other interesting particulars; from mss. Preserved in the State Paper Department of Her Majesty’s Public Record Office, England. London (after John Camden Hotten, 1874): http://www.archive.org/stream/originallistsofp00hottuoft#page/n5/mode/2up.

Dunton, John

1686 Letters Written from New England, Prince Society Publications Issue 4, Ayer Publishing, North Stratford NH.

Erkkila, Barbara

1954 Archaeologist Unearths Ancient Relics of Dead Town. Gloucester Daily Times, August 6, 1954; Dogtown Diggers Start Excavation at Mill Site. Gloucester Daily Times, August 28, 1954.

Family Search

2021 Essex County Genealogy, Courthouse Records and Ancestry; Essex County, Massachusetts History, Records, Facts, Genealogy and Ancestry: https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Essex_County,_Massachusetts_Genealogy.

Felt, Joseph B.

1862 Indian Inhabitants of Agawam: Read at a Meeting of the Essex Institute, held at Hamilton, August 21, 1862. Essex Institute Historical Collections 4: 225-228; Biographical sketch of John Endicott; Opinions on Winthrop and Endicott and who was the first governor of Massachusetts. Essex Institute Historical Collections 5:73, 8: 96, and 15: 298.

Gloucester MA Archives

Town Records, including First Settlement (CC119); Military 1623 (CC87); Town Records Vol. I 1642-1714, including pre-1701 Land Grants (CC59); Town Papers Miscellaneous CC31, CC265; Selectmen’s Records 1699-1721; Minutes of Selectmen’s Meetings 1682, 1684; 1642 Surveying, Maps, Public Property (CC12, CC158); and 1790 Census (CC202), Gloucester City Hall; Vital Records to the end of the year 1849: http://www.ma-vitalrecords.org/MA/Essex/Gloucester/.

Gloucester Magazine

1978 In 1822 Maine Indians still summered on Cape Ann, Gloucester Magazine 1 (4): 14.

Gloucester Telegraph

1831 Indian Rights, January 22, 1831.

Gott, Lemuel, and Ebenezer Pool (John W. Marshall, ed.)

1888 History of the Town of Rockport: as comprised in the centennial address of Lemuel Gott, M.D., extracts from the memoranda of Ebenezer Pool, Esq., and interesting items from other sources, Rockport Review Office, Rockport MA: https://archive.org/details/historyoftownofr00gott_0.

Heitert, Kristen, Gretchen M. Pineo, and Dianna Doucette

2020 Archaeology of Dogtown Historical and Archaeological District National Register Form, The Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc.: https://www.gloucester-ma.gov/DocumentCenter/View/5374/Dogtown-Historic-and-Archaeological-District-NR- Form-Final?bidId=

Hurd, Duane Hamilton

1888 History of Essex County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men, J. W. Lewis & Co, Philadelphia PA.

Lane, Charlotte Augusta

1925 Indians. Unpublished handwritten deposition in the Gloucester Archives, Gloucester (MA) City Hall.

Lepionka, Mary Ellen

2013 Unpublished papers on Cape Ann Prehistory, Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 74 (2): 45-92.

Leveillee, Alan

1988 An Intensive archaeological survey of the proposed Essex Bay Development Area, Gloucester, MA, Massachusetts Historical Commission #829, Boston.

Massachusetts Archives Collection

Vol. 113 (Towns: 1693-1729), incl. Gloucester Records [1642-1874], records of deeds (1701-1914), and the Commoner’s book (1707-1820). Examples include “Records of land grants, division bounds, thatch lots, herbage lots and wood lots, and highway”, and “Minutes of meetings of Proprietors of Common Lands”, Massachusetts Archive Collection Microfilm A 632.

Pool, Ebenezer

1823 Pool Papers, Vol. I. Typescript Mss. in the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester, MA (original is in the basement of the Sandy Bay Historical Society, Rockport, MA).

Pringle, James R.

1892 History of the Town and City of Gloucester, Cape Ann, Massachusetts. (Self-published in Gloucester, MA, originally under the title Souvenir History of Gloucester Mass 1623-1892): https://archive.org/details/historyoftowncit00priniala.

Saville, Marshall H.

1920 Indian Relics from Newburyport and Gloucester, American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1 (Boston).

Speck, Frank G.

1923 Massachusetts Indians, especially relating to Cape Ann, Gloucester Daily Times, Aug. 4.

Swan, Marshall

1980 Town on Sandy Bay, Phoenix Pub., Manila, Philippines.

Vickers, Daniel

1994 Farmers & Fishermen: Two Centuries of Work in Essex County, Massachusetts, 1630-1883. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC.

Waters, Henry Fritz-Gilbert

1882 The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, Vols. 36; 45; 51: New England Historic Genealogical Society, Boston MA: http://wiki.whitneygen.org/wrg/index.php/Archive:The_New_England_Historical_and_Genealogical_Register.

William, Salem

1905 Some account of the Agawam Tribe, in George Francis Dow, ed., Essex Institute Historical Collections 4: 225; 6: 208.